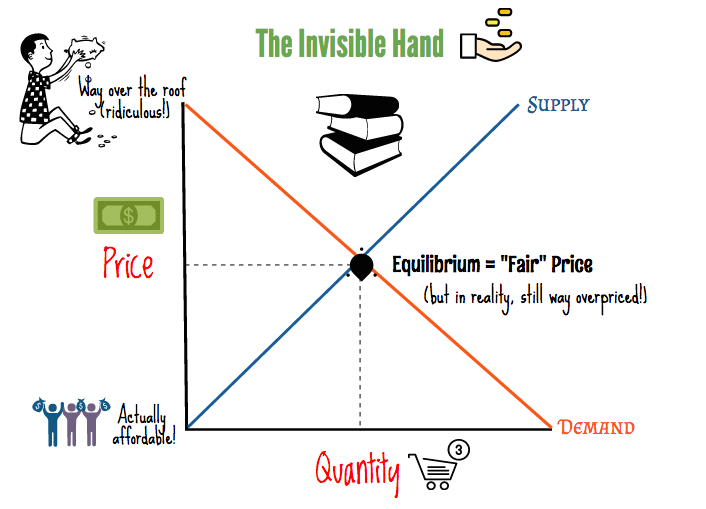

The vocabulary of macroeconomics-“the economy,” “the trade sector,” “the fiscal and monetary policy levers”-makes it seem as if the economy were a large machine with dials that can be turned just so to maximize the interests of society at large. The proof is in what the late Steve Horwitz called the double thank you.Īnd it’s important that these transactions be on the participants’ own terms. Let people trade on their own terms, and they will gain. This is evidence that we both gain from the transaction, even though the exchange itself does not create any new food or any new cash it just changes the ownership titles. And we will both say “thank you” when the deal is struck. The butcher will fill my belly, in exchange for money. The simplest and most powerful mechanism powering the invisible hand is the mutual gain that people expect when they trade with one another. If the conditions for a perfectly competitive market cannot be obtained, this explanation for the invisible hand can feel like a raised middle finger.īut invisible hands have more than one digit. It gives the impression that this is the one and only reason to believe the invisible hand of the market can channel individual self-interest into greater social good. But it’s also not realistic in a lot of markets. Whew!įor many economists, this explanation is elegant and interesting, especially when translated into the language of mathematics. When marginal costs equal marginal benefits, then society’s welfare is maximized. So, the profit-maximizing competitive firm sets its price equal to marginal cost. Firms maximize their profits when the cost of the marginal unit just equals the revenue it generates. Thus, the marginal revenue curve is also flat and is identical to the demand curve. Each unit sold generates the same amount of revenue. From its perspective, the demand curve looks perfectly flat. The textbooks offer a technical-and, for many, inscrutable-explanation: A competitive firm has no choice but to charge the price that is set by the market. In the textbooks, there is one dominant explanation of how the invisible hand works: In a competitive market, price gravitates toward marginal cost, and this maximizes social welfare. So, in an effort to move from blind faith to informed understanding, let’s consider five mechanisms that explain how the invisible hand of the market works. Instead, they’ve built and then tested theories that explain how the invisible hand achieves its wonders. We can appreciate these achievements without attributing them to a “benevolent superhuman intelligence.” Economists have not spent 245 years unthinkingly genuflecting to the invisible hand. And just as with the actions of a physical hand, there are many mechanisms that work to make markets function. Over the past 25 years, the invisible hand of the market lifted 110,000 people out of poverty every day. The invisible hand of the market also works wonders.

But to appreciate how the hand works these wonders, one must think through the mechanisms at work: At the direction of 200,000 neurons, 34 muscles (each supplied with oxygen by a vast network of blood vessels) power the movement of 29 bones and-ultimately-five fingers. We know the human hand can catch a fly ball, perform coronary revascularization and play Vivaldi. Why, then, do so many mistake the economist’s awed wonder at the invisible hand of the market for unquestioning faith? Perhaps it is because we economists do not talk enough about the causal mechanisms at play.

But no one could rightly accuse the famous atheist of having inscrutable faith in the benevolence of natural processes, no matter how wonderous he finds them. There can be no doubt that Dawkins has reverence and wonder for the natural world. It is truly one of the things that makes life worth living. It is a deep aesthetic passion to rank with the finest that music and poetry can deliver.

The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable. Consider Richard Dawkins’s paean to science in “ Unweaving the Rainbow”: The precision alone of the Invisible Hand demands from us reverence and wonder.īut there is a difference between awed wonder and unquestioning religious faith. They are the product of some inscrutable but benevolent superhuman intelligence. They are miracles in which we must have faith. “I, Pencil” treats supply chains in the language of religion. Earlier this fall, Declan Leary wrote an essay in the American Conservative upbraiding the late Leonard Read, author of the famed essay, “ I, Pencil.” According to Leary, Read displays a quasi-religious, unquestioning faith in the invisible hand of the market:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)